The “Estoria de España” As a Work of Art

What sources did Alfonso use? What are the ideological beliefs that resonate within the Estoria? What images of Islam and Muslims are conveyed in the text? Which later works have been influenced by the text? Discover how the Estoria de España has been reconstructed through the ages.

The Estoria de España tells of the events Spain and related places dating back to its legendary origins. The work begins with details that refer to Genesis, with references to such events as the expulsion from Paradise, the Great Flood and the Tower of Babel. From this point until the beginning of the Carthaginian rule (chap.16), Alfonso’s historians made an extraordinary effort to reconstruct the mythical origins of the Peninsula, based on sources that we no longer have today. For example, a number of details, and sometimes entire stories, included in the first chapters have origins that the first editors of the Estoria considered to be “probably Arabic”. What is certain is that they are intensely traditional narrations that recount well-known folkloric tales: amongst them the founding of Seville by Hercules and Cesar, the population of the island of Cadiz by Espan and his daughter Liberia (display case 1 – object 3), the amazing Leyenda del rey Rocas (Legend of King Rocas) and the realm of the mysterious “almujuces” (fire worshipers).

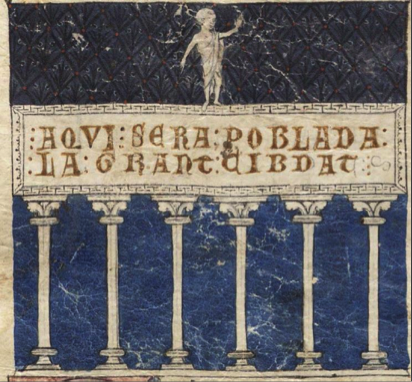

In the story about the origins of Spain, the Estoria highlights the major role played by Hercules. The fourth chapter, in fact, is exclusively devoted to distinguishing between “the three Hercules that the world had”, and central to this chapter are the twelve famous deeds. In effect, the chapter is about Hercules as the first lord of Spain, the first in an unbroken succession of rulers the most recent of which is Alfonso himself. Specifically, it tells of Hercules’ role in founding and populating cities such as Cadiz, Seville and La Coruña. Given these credentials, Hercules could not be forgotten in the king’s ambitious plans for the splendid codex of the Estoria that has been conserved today. Although it is fragmentary and incomplete, since there only appear to be six of the approximately one hundred miniatures that were planned, one of the few images included is a portrait of the Greek hero strangling a pair of lions: “the two lions in the Nemea forest”. The disproportion between the size of the man and that of the animals, makes it seem as if these lions, in the words of a modern art historian, are “simple kittens”.

In the story about the origins of Spain, the Estoria highlights the major role played by Hercules. The fourth chapter, in fact, is exclusively devoted to distinguishing between “the three Hercules that the world had”, and central to this chapter are the twelve famous deeds. In effect, the chapter is about Hercules as the first lord of Spain, the first in an unbroken succession of rulers the most recent of which is Alfonso himself. Specifically, it tells of Hercules’ role in founding and populating cities such as Cadiz, Seville and La Coruña. Given these credentials, Hercules could not be forgotten in the king’s ambitious plans for the splendid codex of the Estoria that has been conserved today. Although it is fragmentary and incomplete, since there only appear to be six of the approximately one hundred miniatures that were planned, one of the few images included is a portrait of the Greek hero strangling a pair of lions: “the two lions in the Nemea forest”. The disproportion between the size of the man and that of the animals, makes it seem as if these lions, in the words of a modern art historian, are “simple kittens”.

One of the most fascinating tales in the Estoria is the Legend of King Rocas. The source remains unknown, although it is most likely Arabic, and it is spread across chapters 11,12 and 13 of the work. The tale narrates the unfortunate events of King Rocas, who left Eden in search of wisdom, whereupon he finds himself sharing a cave with a dragon in the place that would become Toledo. This is not the only instance of a dragon in the Estoria: two more are mentioned during Roman history: these were killed by San Silvestre and San Donato, and there is an “angry serpent that came by the bloody air, it was so fierce, and had fiery breath” which frightened the Spaniards before the battle of Hacinas in the time of Count Fernan Gonzalez. Moreover, the inclusion of the Legend of King Rocas in the general plot of the Estoria produces a digression, that is, a story within a story. This can be seen in the reference to the two towers that Espan’s son-in-law Pirus had founded in the place that would later become Toledo: “the one that is now the alcazar and the other San Roman”. To explain the emergence of these towers, the text uses an abrupt flashback:

During the composition of the Estoria, a process of summarising, comparison and combination of the texts was put into place. Due to the quantity and quality of material in the Estoria, this process exceeded that of previous reconstructions of the past.

There were many sources that were identified with the work, but two works in particular were the building blocks for the Estoria: the basic foundation for the work was the Historia de rebus Hispaniae (The History of the Deeds of Spain) by the Archbishop of Toledo, Rodrigo Jimenez de Rada (c. 1170-1247); and this was supplemented by the Chronicon mundi (Chronicle of the World) by Lucas de Tuy († 1249).

As for Roman sources, works by classical authors such as Floro, Veleyo Paterculo, Justino and Eutropio, as well as Late Antique texts, especially the Historia adversus paganos by Paulo Orosio, and the chronicles of Paulo Diacono, Eusebio Jeronimo, Jordanes and San Isidoro, were used. Alfonso also used more contemporary authors such as Sigebert de Gembloux, Hugucio de Pisa, Martin Polono and Vicente de Beauvais, whose famous Speculum historiale allowed Alfonso to integrate other important works such as Suetonius' De vita Caesarum. Moreover, the Classic Latin sources included some poetic texts: Farsalia by Lucan, and the Heroides by Ovid. Additionally, medieval Hispanic sources used include the Poema de Fernan Gonzalez and the Historia Roderici, as well as a work by Ibn Afaray about Valencia in the time of the Cid. Furthermore, some details were added which were taken from Liber regum and other chronicles and annals, and even some from the oral tradition.

A large proportion of the Estoria is based on extensive passages from epic narratives. Despite the negative evaluation of these texts, as they were thought to invert “the truth” of Latin, many of them are used in the Estoria as they already formed part of a collective memory of the past. In this way, they supported Alfonso’s desire to include the largest quantity of sources possible. In fact, the king himself considered them to be useful and recommendable for chivalric education in his work the Partida II, where it is stated that it is advisable for knights to sing during dinner.

A curious example of the research work that the king’s collaborators had to undertake is a receipt for the copy of Farsalia by Lucan and the Heroidas by Ovid, for the use in the Estoria de España and the General estoria. This document, dated to early 1270, helps us to date the beginning of the Alfonsine historiographical work.

Once the sources were gathered, they were prioritised and combined. The difficulty in carrying out this task is highlighted by a quote from the chronicles itself, when it discusses whether Seville or Toledo should be the primatial see in Spain:

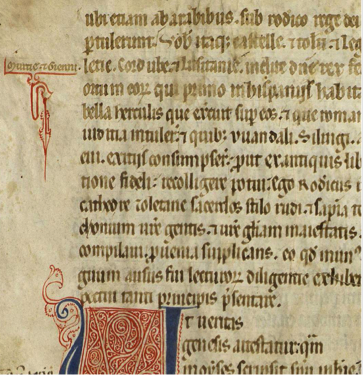

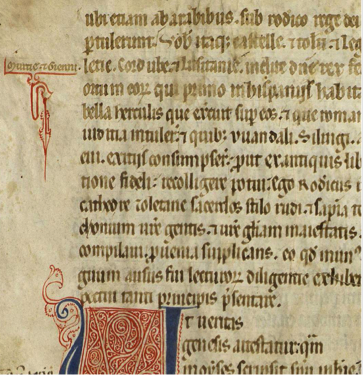

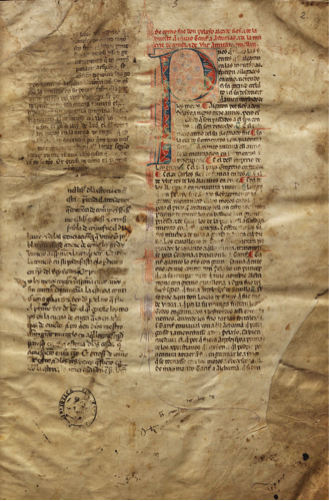

Manuscript 143 from the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla de Madrid holds an especially interesting version of Historia de rebus Hispaniae (The History of the Deeds of Spain) by the archbishop of Toledo, Rodrigo Jimenez de Rada. It is a direct copy of the original manuscript, which was kept until the sixteenth century in the monastery of Santa María de Huerta in Soria, where Rodrigo’s work had been written, although the original has been lost. We know that Rodrigo had included some hand-written updates in the margins of some folios of this lost manuscript. Manuscript 143 retains the draft structure of the original, including the text and the marginal corrections, as though it were a medieval photocopy. For example, in the image of the fragment of f. 2v of the manuscript you can see marginal notes ("Murcie et Gienni"/ 'Murcia and Jaen') added in the same place where Archbishop Rodrigo would have annotated his own copy. Given that the first composition of the text was completed in the spring of 1243, these updates would have been incorporated between 1246 (the date of the conquest of Jaen) and June 10th 1247 (the death of Rodrigo). Furthermore, the fact that this copy of Historia de rebus Hispaniae is the second most-used source by Alfonso in the Estoria, judging by some textual peculiarities that they share, suggests that this was definitely the manuscript used by the collaborators in the composition of the Estoria. In the opinion of the renowned Estoria scholar Diego Catalán, it had probably been copied specifically in order to be used in Alfonso’s scriptorium.

One of the most unpayable debts that the Hispanic culture (and in particular in the history of medieval histories) has to be Estoria de España, as we have been saved from forgetting various epic poems due to the prose-reworking of them, as none of their original manuscripts have been conserved. For example, Estoria de España includes details, or narrations, of events and themes that relate to the French epic (Mainete, Bernado del Carpio and Roncevalles) as well as others which narrate about the Hispanic epic (Los infantes de Salas, La muerte del infante García, Las particiones del rey don Fernando and Mio Cid). Below is an example of prose about the Poema de los infantes de Lara: the famous account of the cucumber that was filled with blood as Dona Lambra tried to avenge her shame of Gonzalo Gonzalez, the youngest of the infants, and it ends with a tragedy.

The Estoria is also very geographical. From this “spacial” aspect, there are terrestrial indications within the work that describe Europe and Spain at the start of the text, as well as hundreds of place names that it lists. In a similar sense, there are a great quantity of announcements and legends, populating and naming of cities, which, despite the details at the start of the text, recur throughout Estoria. For example, already in Alfonso III’s time, in referencing the Great King’s population of Zamora, the story of the huntsman that attacked a black cow in the presence of the King was taken from el Toledano, with the expression “Ca mora” (literally meaning “How black!”), in reference to the colour of the animal, and so it inspired the King to name the city ‘Zamora’.

The idea of ‘the centre’ resonates throughout Estoria, which in itself surrounds the tangible country -Spain. The country in itself is located centrally in the world, making it a magnet for universal news as it is already in the centre of things (remember that during the birth of Christ there was a divine cloud above the peninsular sky; display case 1, object 2). From this perspective, it can be agreed that Estoria de España has a larger focus on place rather than time, which is not the case in la General estoria as it is structured upon the function of the six ages of the world. This historical aspect was especially new, and so, as indicated by Diego Catalan “for the first time in Christian historiography, [Alfonso X] based the separation of a national history from the history of the world in a trans-historical identity of a vital abode called Spain.”

A good example of Alfonso’s view of the world this is that of Nero and his uprising against the emperor. Cordoba had been in a state of unrest, and when Nero finally crushed the uprising, he wondered if he should burn the culprits – the wise men. He was advised not to due to “the nature of the wold”, which determines that if you kill wise men, others will be born in their place.

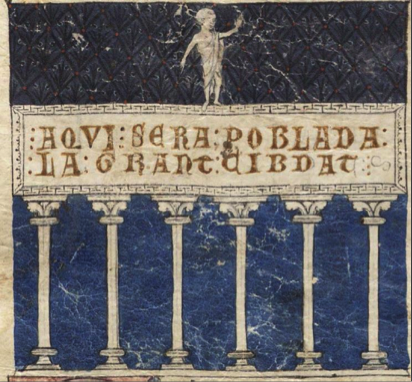

There is no doubt that Alfonso preferred some cities more than others. Specifically, his favourites were Toledo, Murcia and Seville. He saw the population of the first, the old Spanish Visigoth capital and “centre of Spain”, where he centralised many of his cultural initiatives (such as the astronomical observatory that was in use from 1262 until 1272 for las Tablas alfonsíes; display case 2, object 3). He conquered the second, Murcia, in 1243 and afterwards he was educated by the teacher al-Riqutí (display case 1, object 6), and now his entrails and heart rest in the cathedral of Murcia. At the same time, the city that captivated him the most was Seville; his father had conquered it in 1248 and it was the old Muslim capital, where his body now rests. Alfonso had built the shipyards there, which formed the fleet to undertake the African Crusade, and in 1245 a studio was developed where Muslim and Christian teachers taught general Latin and Arabic. In all probability, Seville was the destined capital city under the reign of Alfonso. This is suggested in the story about the foundation of Seville in Estoria, given that Julius Cesar dominates the tale. One of the miniatures from manuscript E1 from the royal scriptorium represents the monument that Hercules made to highlight the significance of the place, where after it would be built by the Roman Emperor.

There is no doubt that Alfonso preferred some cities more than others. Specifically, his favourites were Toledo, Murcia and Seville. He saw the population of the first, the old Spanish Visigoth capital and “centre of Spain”, where he centralised many of his cultural initiatives (such as the astronomical observatory that was in use from 1262 until 1272 for las Tablas alfonsíes; display case 2, object 3). He conquered the second, Murcia, in 1243 and afterwards he was educated by the teacher al-Riqutí (display case 1, object 6), and now his entrails and heart rest in the cathedral of Murcia. At the same time, the city that captivated him the most was Seville; his father had conquered it in 1248 and it was the old Muslim capital, where his body now rests. Alfonso had built the shipyards there, which formed the fleet to undertake the African Crusade, and in 1245 a studio was developed where Muslim and Christian teachers taught general Latin and Arabic. In all probability, Seville was the destined capital city under the reign of Alfonso. This is suggested in the story about the foundation of Seville in Estoria, given that Julius Cesar dominates the tale. One of the miniatures from manuscript E1 from the royal scriptorium represents the monument that Hercules made to highlight the significance of the place, where after it would be built by the Roman Emperor.

As a consequence of the violence of King Rodrigo and the betrayal of Count Julian, Muslims were able to invade and this resulted in a “loss of Spain”. And so, Alfonso included it in Estoria as an exciting praise of his homeland. It closely follows el Toledano (which embraces the tradition of laus Hispaniae that dated back to San Isidoro). Alfonso’s text surpasses that of the source when listing the quantity and quality of benefits that Spain received; and here it ends in an intimate and heartfelt invocation: “Oh, Spain, there are no words that can praise you enough!”

The pages of Estoria also highlight an ideology that fits in with what we know about the King’s political stance.

On one hand, the structure of Estoria perceives the King as the centre of his own political position. The distribution of the content conveys this notion of ‘lordship’, so that everything occurs chronologically in relation to the succession of rulers (the order follows this structure: Greeks, “almujues”, Africans, Romans, Barbarians and Goths). And within these ‘rules’ the events also correspond to a yearly chronological sequence, whereby the peninsular ‘rules’ have been added (including al-Andalus), including the three lines of Christian heirs: popes, emperors and kings of France.

Another ideological characteristic is the prioritisation of the kingdom of Castile and Leon in respect to the other peninsular kingdoms. This favouritism is already present in the main source for the text (The History by Jimenez de Rada), that fits perfectly with Alfonso’s vision ‘Imperium Hispanicum’ that was centred around his own kingdom. This idea is presented in the structure, as particular rulers of the peripheral kingdoms are not included in the general history, they are only present in an individual tale that is integrated into the central history.

The last important aspect about the ideology of Estoria is called “neogothicism”. It is the relation between the kings of Asturias (that King Alfonso himself was directly related to) with the lineage of Gothic kings (as the invasion of Muslims had dissolved this continuity). Taken from the two main sources that were previously mentioned, this notion exists due to the fact that Pelayo descended from the Gothic monarchy, and therefore the dynastic line remained. Also, the Gothic people are continuously praised throughout Estoria as proof that the King belonged to the Staufen house through maternal inheritance (display case 1, object4), as a means of his great political project - becoming the Holy Roman Emperor.

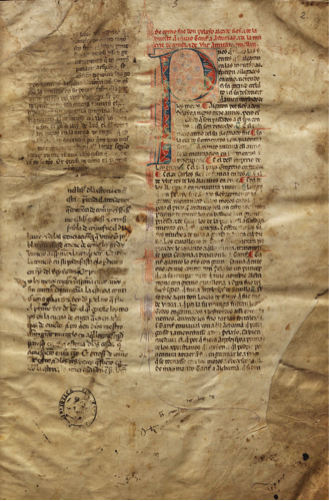

This continuity of the Gothic kings and the kings of Asturias that Alfonso established was not sustained in post-Alfonsine historiography. His son, Sancho IV, immediately acknowledged the indigenous Spaniards over the Hispanic Goths. A few decades after, when Estoria was returned to by Alfonso XI (in the mid-fourteenth century) the Gothic connection is permanently broken. This is shown in the manuscript itself; as a historian in the times of Alfonso XI had hold of the manuscript, which had been continued in the times of Sancho IV. To mark the cut between the Gothic kings and the Asturias kings, he decided to divide the work into two volumes, so that the start of the second volume would begin with the aforementioned Pelayo. And so, he split the manuscript into two books, and in order to head the second one he rubbed away some lines from the previous chapter about Pelayo’s kingdom (as seen in the image below). So, as it was physically separated into two volumes of history, divided by the rule before Pelayo and the rule after him, in order to highlight the rule of Asturian kings, rather than the Gothic kings, in the origins of the monarchy of Castile and Leon.

The Royal Chancery possesses some documents that are considered a ‘treasure’ of Alfonso’s prose due to the vividness of its content. We have included a fragment here about a privilege granted by the King in Palencia in the spring of 1274 to the town of Pampliega. With the cause of having been ‘robbed’ of the body of the King Wamba, that six centuries after having been buried in the monastery of San Vincente of that town, it was moved to Toledo by Alfonso as it was his father’s desire. Alfonso’s description of those events, carried out at night by clerics, noblemen and villains, is pure gold. Estoria, therefore, proves Alfonso’s initiative to honour royal dignity and the memory of the Spanish king, particularly the Gothic ones.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Peninsula saw the meeting of two great civilsations: Christianity and Islam. After the Muslim conquest of 711, Islamic culture and the Arabic language spread throughout the land. For many centuries, Muslims and Christians came into contact with one another. Relations were not always amicable: there were often violent struggles and bloody battles between Christian and Muslim armies. However, there also were periods of co-operation and peaceful coexistence. In any case, the all-concompassing concept of Alfonsine historiography (the ambition to compose a history of all the "Spaniards") demanded the inclusion of the history of Iberian Muslims since "our Estoria de Espanna is the history of all of the kings of Spain and their doings [...] Moors as well as Christians, and even Jews where this is appropriate".

The Estoria has many stories to tell about Spain's Muslim rulers. It recounts the life of the Prophet Muhammad, the rise of the Islam and its arrival in Spain. Many stories tell of the long struggle between Christian kings and their Muslim rivals. Mighty armies clashed, towns were plundered and vast territories were conquered by both religions. But Muslims were not simply loathed enemies of Christendom: the Estoria recognises the many achievements of the Muslims. The great military leader Almanzor, for example, was admired by Christians for his brilliant successes in battle. The Estoria also tells of the devotion and friendship between the Muslim king Almemon of Toledo and the Christian king Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile.

Generally the attitude towards the Jewish community in Estoria is quite anti-Semitic (corresponding to the medieval mentality). They particularly dominated the Roman history until the destruction of the Temple of Titus and Vespasianus, and afterwards their monarchy and territory are dissolved. Occasionally they are criticised for being greedy and murdering Christ (for example, it says “there is no one more greedy than the Jews”). Furthermore, there is a tale about a sacrilegious Jew and the Jewish involvement in an antichrist conspiracy. Also, in a praise of Julian Pomerio, Archbishop of Toledo, it says “he left among the Jewish people and so he was seen as a rose between thorns”. However, it is well known that the Jews played a role Alfonso’s intellectual project. Their crucial role was translating Arabic wisdom into Castilian Spanish. And instance of this collaborative work is seen in the manuscript of the Libros de ajedrez, dados e tablas (Biblioteca de El Escorial, ms T-I-6) in which we can see three copyists working in the royal scriptorium: a layman, and priest and Jew identified by his clothing.

There are some moments in the Estoria that invert this general hostility towards Muslims. This is seen in the story about the friendship and trust between Alfonso VI and King Mamun of Toledo; when Alfonso VI seeks refuge in Toledo from his brother Sancho. The story is based on a mutual oath of love and honour, where religious differences are put aside.

The historical work that was undertaken by the King also contributed to his pursuit of knowledge. The prologues to his two historical texts commemorate knowledge and wisdom: “It is natural for men to crave all the knowledge of the world […]” (General estoria); “The old wise men from the beginning of time found knowledge and other things […]” (Estoria de España). This intellectual dimension was definitely contemplated in the composition of the work, as it is treated before other aspects in an ideological and political order. Moreover, it is known that the “gnostic component” of medieval literature overflows into “wisdom literature”, which is known for its doctrinal and didactic function by remembering the facts of the past. For example, magistra vitae (life-teacher), teaches people how to live morally according to vices and virtues.

The historian Francisco Rico states that “the reflexion of knowledge and wise men is everywhere in la General estoria”; it is also applicable to the Estoria de España. Even the Latin verses that introduce the work include this notion of wisdom, while the whole prologue is devoted to gnosis. Furthermore, there are numerous passages praising wisdom and wise men, including stories where they are the main character. For example, King Rocas, who had left Eden in search of wisdom, meets Tharcus who confesses that he would prefer to eat with his own people before accepting Rocas’ invitation of eating half of the ox that the dragon brought in the cave, excusing himself with “Such a life I lead, but I have it by vice, and by love of knowledge” (display case 3 – object 1).

The Great Chain of Being, which explains the divine order of living and non-living organisms, conveys the medieval worldview that was also shared by Alfonso. According to this theory, we can also see man as a microcosm, that is, a small world within himself, and likewise, the world can be perceived as a human entity. This is better explained through the image by Opicinus of Canistric (1296-1253) who designed a series of maps, demonstrating the human form in relation to Western geography.

Another relevant aspect in the Estoria is the inclusion of narrations of wisdom. There is a rich set of stories that have an educational value, whereby the main characters are often wise men. We have included an example here that corresponds to Capítulo de Segundo filósofo, known in the Western world thanks to the Latin translation of the Greek text by Willelmus, a monk of Sain Denis, in the 12th century (Vita Secundi Philosophi). The collaborators of the Estoria seem to have been aware of this historical account; upon the retelling of the exploits of Julius Ceasar and Pompey, the diversion of the main theme is justified, as people are able to learn from the examples of punishment.

The history of Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Spanish literature would not be the same without the Estoria de España. The Estoria projected the creative genre of the chronicles of Alfonso; this genre was continued after his death, throughout the 14th and 15th centuries using the historiographic mode of the Wise King. Examples include la Crónica de Castilla (c.1300) or la Crónica de 1344 (display case 4, object 5). Thanks to Florian de Ocampo’s edition of the Estoria in 1541, much of its content was exploited by Lorenzo de Sepulveda in the composition of his Romances nuevamente sacados de historias antiguas de la Cronica de España (Ballads derived from the Ancient Stories of the "Chronicle of Spain". These ballads were written in “Castilian meter and in the tone of old Spanish oral ballads, in order to make them accessible to all. This ballad had a national and historic theme, which developed the poetic subgenre of the scholarly ballad. This subgenre had great success during the second half of the 16th century, including in works such as the Romancero historiado by Lucas Rodriguez (1580), and it was even used as late as the early 17th century.

Finally, the plays of the Golden Age also used the Estoria de España in search of plots for their comedies. For example, the famous play by Lope de Vega El mejor alcalde, el rey, about an honourable villain who has to appeal to the king for help when the lord of the lands commits a crime against him. Lope’s work is a dramatic development of a story from the reign of Alfonso VII that the Wise King included in the Estoria from Lucas de Tuy’s work Chronicon mundi.

The Estoria de España was used to transmit themes of the famous Cid to the modern world. The work itself used sources such as Las particiones del Rey Fernando, the Cantar de Sancho II and a version of the Cantar de Mio Cid (which was very similar to the famous manuscript by Vivar). Likewise, it used the Latin biography of the hero, known as the Historia Roderici (1180) and another work, la Cronica najerense (1185). It also used the work by the Arabic Historian Ibn Alfaray about the Cid’s territory in Valencia, as well as la Elegía de Valencia by Alwaggashi (1094). Finally, it used the brief text from Navarra called Linaje de Rodrigo Diaz (1094) and also the Leyenda de Cardeña, a series of semi-hagiographies about Rodrigo Diaz composed in the monastery of San Pedro in the middle of the 13th century. These works would have remained unknown today if it was not for the Estoria, as the original versions have been lost; between them there are the Leyenda de Cardeña, that tells one of the more memorable episodes of the life of the hero: the famous victory of the Cid after his death. This narrative was so striking that it moved the American film director Antony Mann to use it in the closing scene of El Cid. This famous work of cinema featured Charlton Heston and Sofia Loren, and included academic input from Ramon Menendez Pidal (a distinguished scholar of Spanish history). In short, the script of this well-known film would not have been the same without the work of the Wise King.

We have included the aforementioned passage from the Estoria (taken from Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy) that inspired Lope de Vega’s comedy El mejor alcalde, el rey (The Best Mayor, the King). It summarises that Alfonso found in it a story of its legal formation (which corresponds to the king’s task in his kingdom) and because of this, he saw sufficient reason for its inclusion in the chronicle.

In the beginning was The Cid

In the second section of this display case we mentioned the importance of the Estoria de España for our knowledge of the medieval Spanish epic. One of the epics incorporated into the Estoria is the Mio Cid, in a versions very similar to that of the famous Vivar manuscript. In this clip, you can hear the beginning of the poem, in a recitation by the musicologist Antoni Rossell.

The Imagined Peninsula

Hercules the Founder

Miniature in which Hercules is seen strangling two lions. Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, ms Y-I-2, f. 4r.

To Find Out More

Ana Domínguez Rodríguez, «Hércules en la miniatura de Alfonso X el Sabio», Anales de Historia del Arte, 1 (1989), 91-104.Dragons in the Estoria de España

One of the most fascinating tales in the Estoria is the Legend of King Rocas. The source remains unknown, although it is most likely Arabic, and it is spread across chapters 11,12 and 13 of the work. The tale narrates the unfortunate events of King Rocas, who left Eden in search of wisdom, whereupon he finds himself sharing a cave with a dragon in the place that would become Toledo. This is not the only instance of a dragon in the Estoria: two more are mentioned during Roman history: these were killed by San Silvestre and San Donato, and there is an “angry serpent that came by the bloody air, it was so fierce, and had fiery breath” which frightened the Spaniards before the battle of Hacinas in the time of Count Fernan Gonzalez. Moreover, the inclusion of the Legend of King Rocas in the general plot of the Estoria produces a digression, that is, a story within a story. This can be seen in the reference to the two towers that Espan’s son-in-law Pirus had founded in the place that would later become Toledo: “the one that is now the alcazar and the other San Roman”. To explain the emergence of these towers, the text uses an abrupt flashback:

And these [towers] were made by two brothers, sons of a king called Rocas from the Eastern world to the part they call Eden, there, or so the stories say, is paradise where Adam was made. And this King had such great pleasure from learning that he left all of his kingdom and all that he had in order to go to another land to gain more wisdom. And so he found a land in the North-East, among the seventy pillars; thirty of which were made of brass and forty were made from marble. They were on land and had inscriptions around the perimeter that told of knowledge and the nature of things and who had made them.

And Rocas, when he saw them, sampled them and translated all of them and then he made a book that he brought with him to discover many things that had happened, and he did great wonders. So when people saw him he performed miracles and so everybody came to him, and they plagued him so much that he fled from them and was hiding from one land to another until he arrived in Troy for the first time, before it was destroyed, and he did great and noble deeds and then he started to laugh. And the people asked him why he laughed, he said that if they knew what was to come that they would not be ploughing the fields. Then they took him to King Leomedon. The King asked him why he said those words. He said that he told the truth, that those people will die by sword and the buildings will burn in flames.

When the Trojans heard this they wanted to kill him, but the King thought he said it out of madness and in the end he took him and put him in chains to see if he was right, and he ordered men to guard him. And he, fearing death, knew what to do with those who guarded him. And so he cut the chains and he went on his way. He came by a place (that was later founded as Rome) and he wrote four letters on marble that said ‘Rome’. And these letters were found and after Romulo found it and it pleased him because it was similar to his name, so he called it Rome.

What happened when Rocas was in the cave

After Rocas had done this, he headed West until he arrived in Spain and he walked all around the mountains and the seas that surrounded it. And then he went to Toledo, and he saw that it was a more central part of Spain than any other place, and it had a very big mountain. And he knew that it would be a great city, but he would not populate it. Then he found a cave that housed a very big dragon. And when he saw it, it frightened him and so he asked it not to harm him as they are both creatures of God. The dragon had so much love for him that he hunted with him and he lived there for a long time.

Afterwards, an honourable man of the land called Tharcus, who lived in the mountains of Avila, was hunting on the mountain and found a bear, and so he followed it until he reached the cave. The bear went inside the cave and Rocas, who saw the bear coming, was scared and so he flattered it and asked it to do no harm as there was a dragon who also lived in the cave. The bear bowed before him and put his head into his lap and he began scratching the bear's head. Then the knight that was pursuing the bear entered the cave. And when he saw them together it amazed him, more Rocas than the bear because he had a very long beard and was covered in hair, and he saw him as a very wild man and put an arrow in the bow and wanted to shoot the bear. Rocas asked him, for the mercy of God, not to shoot it. So, when Tharcus heard him speak, he asked him who he was and how he came here. He said that he would not tell him until he agreed a truce with him, and so Tharcus agreed.

So Rocas began to tell him his tale, and when he heard that the King was a noble man he had great pain for him and asked him not to stay here in such danger, and to go with him and marry his daughter, as he had nothing else to offer, and when he died he would leave him all of his possessions. He agreed to do it. And as they were talking the dragon arrived, and when Tharcus saw him he was very scared and wanted to leave. Rocas told him not to as the dragon would do him no harm. And so Rocas went to the dragon and flattered it, and the dragon threw half an ox before Rocas, it kept the other half for its own food. And he asked Tharcus if he wanted to eat some but he declined as he wished to eat with his own company. Rocas replied “such a life I lead, but I chose it for the vice and love of knowledge”. And Tharcus replied “come here and let us leave, this is no longer the place for you”. So Rocas said to the dragon “my friend, I leave you, I am grateful to have lived with you”. And they both left the cave, and never saw the dragon again.

How Rocas left with Tharcus, and the great drought of Spain.

Rocas went with Tharcus and married his daughter, and afterwards they bore two children. One was called Rocas after his father, and the other Silvio. Then Tharcus died and left his possessions to Rocas. Although Rocas had everything he needed, he could not forget the cave, and the memory of the dragon’s friendship, so he went there and built a tower on top of it, and he dwelt there from time to time.

A Historical Encyclopaedia

There were many sources that were identified with the work, but two works in particular were the building blocks for the Estoria: the basic foundation for the work was the Historia de rebus Hispaniae (The History of the Deeds of Spain) by the Archbishop of Toledo, Rodrigo Jimenez de Rada (c. 1170-1247); and this was supplemented by the Chronicon mundi (Chronicle of the World) by Lucas de Tuy († 1249).

As for Roman sources, works by classical authors such as Floro, Veleyo Paterculo, Justino and Eutropio, as well as Late Antique texts, especially the Historia adversus paganos by Paulo Orosio, and the chronicles of Paulo Diacono, Eusebio Jeronimo, Jordanes and San Isidoro, were used. Alfonso also used more contemporary authors such as Sigebert de Gembloux, Hugucio de Pisa, Martin Polono and Vicente de Beauvais, whose famous Speculum historiale allowed Alfonso to integrate other important works such as Suetonius' De vita Caesarum. Moreover, the Classic Latin sources included some poetic texts: Farsalia by Lucan, and the Heroides by Ovid. Additionally, medieval Hispanic sources used include the Poema de Fernan Gonzalez and the Historia Roderici, as well as a work by Ibn Afaray about Valencia in the time of the Cid. Furthermore, some details were added which were taken from Liber regum and other chronicles and annals, and even some from the oral tradition.

A large proportion of the Estoria is based on extensive passages from epic narratives. Despite the negative evaluation of these texts, as they were thought to invert “the truth” of Latin, many of them are used in the Estoria as they already formed part of a collective memory of the past. In this way, they supported Alfonso’s desire to include the largest quantity of sources possible. In fact, the king himself considered them to be useful and recommendable for chivalric education in his work the Partida II, where it is stated that it is advisable for knights to sing during dinner.

A curious example of the research work that the king’s collaborators had to undertake is a receipt for the copy of Farsalia by Lucan and the Heroidas by Ovid, for the use in the Estoria de España and the General estoria. This document, dated to early 1270, helps us to date the beginning of the Alfonsine historiographical work.

Once the sources were gathered, they were prioritised and combined. The difficulty in carrying out this task is highlighted by a quote from the chronicles itself, when it discusses whether Seville or Toledo should be the primatial see in Spain:

But there are a lot of writings and they recount many deeds, because the truth of history is sometimes doubtful. Finally, whoever reads it should choose the best writings and these should be put to the test and read.

Medieval Photocopy

Fragment of f. 2v of Historia de rebus Hispaniae by Rodrigo Jimenez de Rada; in the left margin “Murcie et Gienni” ('Murcia and Jaen') has been added on the title of Fernando III. Manuscript 143 from de la Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla (Madrid).

The Recovered Voice

Dona Lambla and her entourage left for Barvadiello. And to please their sister-in-law, the princes were just above Arlanzon hunting with their hawks. And so they had hunted many birds, and they returned to Dona Lamla to tell her. On their way they entered a garden to relax and enjoy themselves whilst they prepared to eat. Gonzalo Gonzalez removed his linen clothes, took his hawk and went for a swim. When Dona Lambla saw him naked she felt ashamed, so she said to her friends “Friends, do you not see how Gonzalo Gonzales walks unclothed? I believe he is trying to make us fall in love with him. If he thinks he can escape unscathed from this he is wrong” And as she said this she called her husband and said “Take a cucumber and flll it with blood, go to the garden or wherever the princes are and smash it into Gonzalo Gonzales’ chest, the one who is holding the hawk, and then come back to me, but do not have fear, I will protect you and so I will take vengeance from this shame, and for the death of my cousin Alvar Sanchez, and everyone will think it is a joke.”

The man did as he was ordered. When the princes saw the man coming, they thought that their relative had sent them something to eat because it had been a while since they last ate. They thought that they were on good terms with her and that she loved them, but they were deceived. And so the man arrived with the cucumber and smashed it into Gonzalo Gonzalez’s chest and the blood smeared all over him and he fled. When the brothers saw this they started to laugh, and so Gonzalo Gonzalez said “brothers, it is very bad of you to laugh, it could have injured or killed me. And if this had happened to one of you then I would not want to live a day more until I had avenged it. And as you joke so much about it in such dishonour, you must repent to God.

And so Diego Gonzalez said “Brothers, we should take advice from our brother, we must not remain sinners as it will be a great dishonour to us. And now we should take our weapons and our armour and go to that man who did this, and if we said that he waits for us and does not fear us then we will understand that it was a joke. But if he has fled to Dona Lambra and she protects him, then we will know that she ordered him to do it, and he will not escape with his life even though she wants to defend him.” So they took their arms and they headed toward to palace. When the man saw them coming, he fled to Dona Lambla and she gave him armour. The princes said “Sister, do not obstruct us from this man by trying to protect him.” She replied “Why? He is my vassal and if he did something bad to you then settle it outside. And while he is in my power I advise you not to harm him.”

They went and took him by force and they killed him in front of her, she could not defend or do anything for him. And the blood from the man’s wounds fell on her corset and clothes, and she was saturated with blood. Then the brothers mounted their horses and told their mother Dona Sancha that they were heading for Salas. So they went, and Dona Lambla used a large chair to cover the dead body, and she cried and grieved for three days with the other ladies, and then she ripped all of her clothes and called herself a widow as she had no husband.

Somewhere in the Estoria

The Estoria is also very geographical. From this “spacial” aspect, there are terrestrial indications within the work that describe Europe and Spain at the start of the text, as well as hundreds of place names that it lists. In a similar sense, there are a great quantity of announcements and legends, populating and naming of cities, which, despite the details at the start of the text, recur throughout Estoria. For example, already in Alfonso III’s time, in referencing the Great King’s population of Zamora, the story of the huntsman that attacked a black cow in the presence of the King was taken from el Toledano, with the expression “Ca mora” (literally meaning “How black!”), in reference to the colour of the animal, and so it inspired the King to name the city ‘Zamora’.

The idea of ‘the centre’ resonates throughout Estoria, which in itself surrounds the tangible country -Spain. The country in itself is located centrally in the world, making it a magnet for universal news as it is already in the centre of things (remember that during the birth of Christ there was a divine cloud above the peninsular sky; display case 1, object 2). From this perspective, it can be agreed that Estoria de España has a larger focus on place rather than time, which is not the case in la General estoria as it is structured upon the function of the six ages of the world. This historical aspect was especially new, and so, as indicated by Diego Catalan “for the first time in Christian historiography, [Alfonso X] based the separation of a national history from the history of the world in a trans-historical identity of a vital abode called Spain.”

A good example of Alfonso’s view of the world this is that of Nero and his uprising against the emperor. Cordoba had been in a state of unrest, and when Nero finally crushed the uprising, he wondered if he should burn the culprits – the wise men. He was advised not to due to “the nature of the wold”, which determines that if you kill wise men, others will be born in their place.

But with all this, Nero’s advisors, and princes and good men advised him. They said “Cesar, the nature of this place is learnt better than some other dweliing. And we have learnt that if you kill these other wise men in Cordoba there will be others, as we understand and know that nature of the Earth and the land and the air and the substance and the stars, and so you should not do such a thing as more damage would be done.”

The Cities of the King

The miniature that represents the risen monument made by Hercules in the place where Julius Cesar would build Seville. Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, ms. Y-I-2, f. 5.

The Eulogy of Spain

The tribute to Spain, as it is compiled of all good things

And every land of every province that God honoured in different ways, and in them He gave His gift. But of the lands that He honoured most, Spain of the Western world was one, and so He filled it with all of those things that a man usually desired. Since the Gods came through the lands, from one part to the next, proving their strength through wars and battles, and conquering many places in the Asian and European provinces. And so places became inhabited and they were well looked after. They looked for the most valuable place, and found that Spain was the best of all and they treasured it more than the others; and that of all the lands in the world, Spain had an abundance of wonders, more than any other land in the world. Moreover, it is closed off at one end by the Pyrenees mountains, that stretch from one part of the ocean to the Tyrrhenian sea. Also in Spain are the Gothic Gaul that is in the province of Narbonne, along with the cities of Rhodes, Albi and Beders that in the time of the Goths belonged to this same province. Furthermore, Africa has a main province, made up of ten cities, called Tangiers, which was under the rule of the Goths as were all these others.

And so this Spain is like God’s paradise, and five rivers flow through it that are Ebro, Duero, Taio, Gudalquevil and Guadiana. And they flow through the big mountains and lands, and valleys, and they are large and wide, and due to the fertility of the land and the waters that flowed through it, there were an abundance of luscious fruits. And throughout the main part of Spain streams and springs run through, and so every place has the use of water. And in Spain there is an abundance of grain, an enrichment of fruits, plenty of fish, flavoursome milk, and these things mean that it is full of deer and game to hunt, and rich with farm animals, gallant horses and useful mules. It is secured with a supply of castles, and produces good wines, a wealth of bread, rich with metals, lead, aluminium, bronze, silver, gold, precious stones, marble stone, salts from the sea and salt mines on the land, and salt in the rocks, and many other shell beads: blue, red ochre, clay, alum and many others are found on the land; elegant silk and everything that can be made from it, sweet honey and sugar made from beeswax, plenty of oil and luxurious saffron. And above all Spain is ingenious, bold and passionate on battlefield, generous, loyal to its leader, diligent in study, elegant in its language, and perfect in everything. There is not a land in the world that has a similar enrichment nor matches any of its strengths, and there are few places in the world that are as great as it. And above all Spain is governed excellently and it especially values loyaly. Oh, Spain, there are no words that can praise you enough! And without the flowing rivers that we have already mentioned, there are many others that culminate into the sea, not forgetting the names of these flowing rivers, such as Miño, which begins and runs through Galixia and enters the sea; and from this rive the province of Miñea arose; and there are many other rivers in Galicia and in Asturias, Portugal, Andalusia, Aragon, Catalonia and in other parts of Spain, that in the end, finish up in the sea. Furthermore, Alvarrazén and Segura, that are in the province of Toledo, finish in the Tyrrhenian Sea; and there is also Mondego in Portugal, which has not been named here. And so this very noble kingdom, so rich, powerful and so honoured, was wasted and destroyed in an attack due to a disagreement between the people of the land, who turned their backs on each other, and so they became enemies and they lost everything. And so all the cities of Spain were taken prisoner by the Moors and they were violated and destroyed by the hand of their enemies.

Gothic Blood

On one hand, the structure of Estoria perceives the King as the centre of his own political position. The distribution of the content conveys this notion of ‘lordship’, so that everything occurs chronologically in relation to the succession of rulers (the order follows this structure: Greeks, “almujues”, Africans, Romans, Barbarians and Goths). And within these ‘rules’ the events also correspond to a yearly chronological sequence, whereby the peninsular ‘rules’ have been added (including al-Andalus), including the three lines of Christian heirs: popes, emperors and kings of France.

Another ideological characteristic is the prioritisation of the kingdom of Castile and Leon in respect to the other peninsular kingdoms. This favouritism is already present in the main source for the text (The History by Jimenez de Rada), that fits perfectly with Alfonso’s vision ‘Imperium Hispanicum’ that was centred around his own kingdom. This idea is presented in the structure, as particular rulers of the peripheral kingdoms are not included in the general history, they are only present in an individual tale that is integrated into the central history.

The last important aspect about the ideology of Estoria is called “neogothicism”. It is the relation between the kings of Asturias (that King Alfonso himself was directly related to) with the lineage of Gothic kings (as the invasion of Muslims had dissolved this continuity). Taken from the two main sources that were previously mentioned, this notion exists due to the fact that Pelayo descended from the Gothic monarchy, and therefore the dynastic line remained. Also, the Gothic people are continuously praised throughout Estoria as proof that the King belonged to the Staufen house through maternal inheritance (display case 1, object4), as a means of his great political project - becoming the Holy Roman Emperor.

Codic[ideo]ology

Folio 2r, manuscript E2. Presenting the deleted lines from the previous chapter in order to separate the Gothic kings from the kings of Asturias.

This continuity of the Gothic kings and the kings of Asturias that Alfonso established was not sustained in post-Alfonsine historiography. His son, Sancho IV, immediately acknowledged the indigenous Spaniards over the Hispanic Goths. A few decades after, when Estoria was returned to by Alfonso XI (in the mid-fourteenth century) the Gothic connection is permanently broken. This is shown in the manuscript itself; as a historian in the times of Alfonso XI had hold of the manuscript, which had been continued in the times of Sancho IV. To mark the cut between the Gothic kings and the Asturias kings, he decided to divide the work into two volumes, so that the start of the second volume would begin with the aforementioned Pelayo. And so, he split the manuscript into two books, and in order to head the second one he rubbed away some lines from the previous chapter about Pelayo’s kingdom (as seen in the image below). So, as it was physically separated into two volumes of history, divided by the rule before Pelayo and the rule after him, in order to highlight the rule of Asturian kings, rather than the Gothic kings, in the origins of the monarchy of Castile and Leon.

Historic Memory

The Royal Chancery possesses some documents that are considered a ‘treasure’ of Alfonso’s prose due to the vividness of its content. We have included a fragment here about a privilege granted by the King in Palencia in the spring of 1274 to the town of Pampliega. With the cause of having been ‘robbed’ of the body of the King Wamba, that six centuries after having been buried in the monastery of San Vincente of that town, it was moved to Toledo by Alfonso as it was his father’s desire. Alfonso’s description of those events, carried out at night by clerics, noblemen and villains, is pure gold. Estoria, therefore, proves Alfonso’s initiative to honour royal dignity and the memory of the Spanish king, particularly the Gothic ones.

As it is standard for a king to honour good and noble men, principally kings who have governed these lands ; I, Don Alfonso, by the grace of God King of Castile, Toledo, Leon, Galicia, Seville, Murcia, Jaen and Algarve, who reigns with Queen Violante, my wife, and our children: Don Ferrando, first-born, Don Sancho, Don Pedro, Don Johan and Don Jaymes, knowing certainly that the noble King Bamba, who descended from the Goths as a lord of Spain and many other lands that he gained from the mercy of God, and his own effort and kindness he arranged the lands and put them in good condition, so that no one defied him nor left any of his lands. Also, he divided his lands into districts and assigned a bishop to each district, as these places already had many disputes and so the King knew this would prevent them and bring peace and assurance. Moreover, before his time was up he had to save his soul before he died, and so he adopted the religion of black monks in San Vicente de Pampliga from the honourable monasteries that Spain had at that time.

And despite this land was lost after the Muslim invasion, the other Kings knew that this was where he was buried, it was especially known to the noble and blessed King Ferrando, my father, as he was taught by the Archbishop of Toledo Don Rodrigo in Istoria de España, and from the people of the town who showed him where King Bamba was buried, in front of the door to the church. And because King Ferrando was so considerate and honourable, he made another door to exit the church so as to not pass over the grave of this King. He wished to move the body to somewhere more honourable, but God took him to paradise before he could complete this task. And so I, Don Alfonso, reigned after him and, knowing all of this, I went to this place as I wanted to prove if it was true, but due to a great rush of events I could not do it. But in 1312, when I was in the courts of Burgos, upon sending knights to the Roman Empire, I left Burgos and I happened to pass by Pampliga, and I wished to prove if he was truly buried in that place where they say, and I sent the priests and the good men of our house and the town to dig it up at nightfall, and God wanted us to find it there where we were told.

And because I saw that the place had no monastery of any religion nor so much as a clergy where he can be buried honourably, nor a church where he can have his own grave I sent him to Toledo to be buried, where, in the time of the Goths it was the capital city and where the old emperors were crowned. Furthermore, it was fitting to send him there as he was one of the most honourable lords who had done so much for Spain. And I, took him from that place where he was formerly buried, for all of the reasons above, and I took him for the right of doing good to those of that town Pampliga, because they were honoured while this King was buried […]. And because this is firm and stable, I send this privilege with our lead stamp. I date the privilege in Palencia, Friday, thirteen days into the month of April, in the year 1312 [...].

To Find Out More

Jeneze Riquer, «Iberia legendaria (6 y 7). La leyenda de Wamba labrador (V y VI)», Rinconete, 4 y 18 de agosto de 2010.Muslims and Christians

The Estoria has many stories to tell about Spain's Muslim rulers. It recounts the life of the Prophet Muhammad, the rise of the Islam and its arrival in Spain. Many stories tell of the long struggle between Christian kings and their Muslim rivals. Mighty armies clashed, towns were plundered and vast territories were conquered by both religions. But Muslims were not simply loathed enemies of Christendom: the Estoria recognises the many achievements of the Muslims. The great military leader Almanzor, for example, was admired by Christians for his brilliant successes in battle. The Estoria also tells of the devotion and friendship between the Muslim king Almemon of Toledo and the Christian king Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile.

...and Jews

Miniature from the Libros de ajedrez, dados e tablas (o Libro de los juegos), showing three copyists from the royal scriporium working: a layman, a priest and a Jew. Ms. T-I-6, Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, f. 1.

Generally the attitude towards the Jewish community in Estoria is quite anti-Semitic (corresponding to the medieval mentality). They particularly dominated the Roman history until the destruction of the Temple of Titus and Vespasianus, and afterwards their monarchy and territory are dissolved. Occasionally they are criticised for being greedy and murdering Christ (for example, it says “there is no one more greedy than the Jews”). Furthermore, there is a tale about a sacrilegious Jew and the Jewish involvement in an antichrist conspiracy. Also, in a praise of Julian Pomerio, Archbishop of Toledo, it says “he left among the Jewish people and so he was seen as a rose between thorns”. However, it is well known that the Jews played a role Alfonso’s intellectual project. Their crucial role was translating Arabic wisdom into Castilian Spanish. And instance of this collaborative work is seen in the manuscript of the Libros de ajedrez, dados e tablas (Biblioteca de El Escorial, ms T-I-6) in which we can see three copyists working in the royal scriptorium: a layman, and priest and Jew identified by his clothing.

A Pact Between Knights

How King Alfonso sought refuge from Almemon, the King of Toledo.

Princess Uracca, upon discovering the imprisonment of her brother, King Alfonso, feared that her other brother, King Sancho, would be killed for detaining him within the kingdom. And so it was that she headed towards Burgos, accompanied by Don per Assurez, to ask the Count to move Alfonso from the prison into the monastery in Saint Fagund. King Sancho approved her request; it was his pleasure to allow King Alfonso to enter the monastery, more for the sake of punishment than goodwill. However, Don Per Assurez advised Don Alfonso to escape from the monastery at nightfall and to head to Toledo to find Almemon, King of the Moors. This king admired Don Alfonso and welcomed him with honour; he gave him many gifts and provided him with all that he needed. And until the death of King Sancho, Don Alfonso remained with King Almemon; now the whole, unabridged tale shall be told. At the beginning, there were three brothers, some of the noblest men in the kingdom of Leon, who were averse to being the vassals of King Sancho. They accompanied King Alfonso on his journey to Toledo as they were sent by his sister, Princess Uracca, to protect him. Their names were: Per Assurez, Gonzalez Assurez and Fernando Assurez, although Don Lucas of Tuy believed that these men were with King Alfonso, much to the satisfaction of king and the will of God.

When he arrived, Almemon, the King of Toledo, paid so much service to King Alfonso and loved him as if he was his own child; he provided him with a lot of money as well as honour. And so Don Alfonso swore an oath and pledged that he would always honour King Almemon and protect him for as long as he remained with him; and so the story goes, King Almemon made the same vow; and so they were both under agreement and swore an oath. And King Almemon built magnificent palaces for Don Alfonso outside the walls and close to the fortress so that it did not distress the people of the city. The palaces surrounded the gardens, which Don Alfonso enjoyed with his Christian knights and associates. King Alfonso, as he admired the benevolence and honour of that knightly and majestic lord of the Moors, King Almemon, in the noblest city at the time of the Visigoths, he began to feel a great heaviness in his heart for this place. He wondered if it was possible to take the power from the Moors if God gave him enough time to do it. Meanwhile, he warred with King Almemon’s enemies and fought with the Moorish Kings. And when there was peace between King Almemon and his enemies, Don Alfonso went to hunt in the forest near the mountains of Toledo and on the banks of the rivers. And now we shall unfold this tale…

The hunt, and the signs that caused the suspicion of Don Alfonso.

At that time there was a great deal of hunting for bears, sows and dear. And whilst walking further up the river, Don Alfonso discovered a place called Brihuega. This place boasted a castle and captivated him as an ample hunting ground, and because this was his passion, when he returned to Toledo he asked the King for this land, to which the King gladly agreed. And there he remained with his Christian riders and hunters. And the dynasty of these occupants remained here until Don Juan III, Archbishop of Toledo, extended the land to the villagers of San Pedro. One day, when King Almemon, accompanied by the other Moors, was loitering around his gardens, he looked out to the city of Toledo and feared that the Christians would be able to conquer such a city. Whilst the King was in the garden, Don Alfonso was nearby as to ensure that the King was well. However, he was under a tree and appeared to be sleeping.

King Almemon, having wandered through the gardens for quite a while, his mind troubled with thoughts of a Christian defeat, came to the tree where Don Alfonso was, and as he was sleeping he did not want to wake him. King Almemon was not protected so he sat in the presence of the Moors and asked them if they believed it was possible that the city could be taken by force. One of them replied “if this city was attacked, we would have enough bread, wine and fruit to last us seven years, but in the eighth year it could well be defeated due to a lack of sustenance.” And under that tree where Almemon believed him to be sleeping, Don Alfonso heard this exchange and it made him wonder about what they said.

One day near Easter, when, according to Mohammad’s law, the Moors are required to kill a sheep. And so King Almemon and his Moors went to the customary place in order to behead the sheep. King Alfonso and his Christian associates accompanied them to honour King Almemon. Don Alfonso and King Almemon remained together. And so the stories say, the Moors remarked what a handsome knight Alfonso was, praising his chivalry. And as he was with King Almemon, two moors on horseback spoke of King Alfonso: “How handsome and skilful a knight is the Christian? He is worthy of being a great lord.” And the other responded: “I dreamt last night that Alfonso rode to Toledo as a knight on a sow.” After he said this, the first deciphered the dream: “I tell you without fail that it forecasts Alfonso as the lord of Toledo.” Meanwhile, all the hairs on King Alfonso’s head stood up.

Don Lucas de Tuy remarked that the Kings were both together, and that this strange incident perplexed King Almemon as he attempted to flatten Don Alfonso’s hair with his own hand; but it is said that the more he tried to subdue it, the more resilient it became. And so after the beheading of the sheep, they returned to the city. Almemon had heard the exchange between the two Moors concerning Alfonso, and on his return to the palace he could not stop thinking about it. So he sent for the two Moors; when they arrived he sat with them and asked them about their conversation during the ceremonial tradition. They repeated every word to the very last detail.

After hearing this, King Almemon sent for the wisest men in the city to come before him and to advise him on what the Moors said; he told them about the dream and the eerie matter of Alfonso’s hair. Upon hearing this, the wise men came to a unanimous understanding; according to these signs Don Alfonso was to become the lord of Toledo, and so they advised the King to kill him. However, King Almemon said that he would do no harm to Don Alfonso, as he came to him with trust and loyalty, so he refused to do it. He stated that he did not wish to break the oath he swore, and King Alfonso had fought strongly in the battles against their enemies, who were thereby defeated. After so much reflection, he called for King Alfonso and asked him to swear that, whilst he lived he would do no harm against him and his children, nor to the people around him. King Alfonso, full of loyalty in his heart, swore this oath and promised him more; he would stand against all men that confronted King Almemon. From then on he trusted in Alfonso, and they became dear friends. Meanwhile, King Alfonso consulted Count Don Per Assurez, his advisor at the time, and asked for his advice about all that had happened. And so we must leave the story here, and return to Don Sancho and his affairs after Don Alfonso left for Toledo [...].

History and Wisdom

The historian Francisco Rico states that “the reflexion of knowledge and wise men is everywhere in la General estoria”; it is also applicable to the Estoria de España. Even the Latin verses that introduce the work include this notion of wisdom, while the whole prologue is devoted to gnosis. Furthermore, there are numerous passages praising wisdom and wise men, including stories where they are the main character. For example, King Rocas, who had left Eden in search of wisdom, meets Tharcus who confesses that he would prefer to eat with his own people before accepting Rocas’ invitation of eating half of the ox that the dragon brought in the cave, excusing himself with “Such a life I lead, but I have it by vice, and by love of knowledge” (display case 3 – object 1).

Microcosms and Macro Anthropos

The Story of Segundo the Mute

In the times of Emperor Adriano there was a great philosopher called Segundo who made a many good books, yet he did not speak. Listen to why.

When he was a child he was sent to schools to read and to stay there for a long time until he was a great teacher. And there he heard that a chaste woman did not exist in the world. And since he finished learning philosophy he returned to his land as a pilgrim with his cape, basket and his staff. And his hair and beard had grown very long. And he sat in his how and his more, nor anyone that was there, recognised him. And he wanted to see if what they said in the women’s schools was true and so he called one of the servants of the case and promised her ten pounds if she arranged for his mother to lie with him. The servant made the mother agree to it that night. And the mother, believing that he was another that wished to sleep with her, put his head between her breasts and he slept next to her the whole night well as if he was next to his own mother. And when the morning came he got up to go on his way and she took him and said: “What! Why did you make me do this?” And he replied “No, my lady, it is not right that I should dirty the glass from whence I came.” And she asked who he was and he responded “It is me, Segundo, your son.” And when she heard this she thought that she could not suffer this great confusion and she fell to her death. When Segundo saw that his words had killed his mother it pained him and he swore that he would never speak again in his life. And he went to Athens to the schools and he lived there and made good books. Emperor Adriano never went to Athens but he knew about his deed and so he sent for him to greet him. And Segundo did not wish to say anything, so Adriano said “Speak philosopher; I wish to learn something about you.” But as Segundo did not wish to speak he sent for one of his guards called Tirpon and said “As this man does not wish to speak, I, the emperor, do not wish for him to live; take him with you and torture him until he dies.” Then he took the guard to one side and said “as he will not want to die, he will be forced to speak. And if you see that he believes you and he responds to you then behead him. If he does not want to speak at the fear of death return him to me.” And so the guard took him to the place where they tormented men and he said “Segundo, why are you mute, and why do you not wish to speak and henceforth live?” And still the philosopher did not speak as he did not value life enough to break his vow. And they arrived at the place where they had to go and the guard said “prepare his neck.” So he took his neck and still he refused to talk.

So the guard took him by the hand and led him to the emperor and he said that Segundo would remain mute until his death. So Adriano thought a lot about how the philosopher could abstain from speaking, and finally he said “because you strongly refuse to talk, take this board and write on it, and you will talk with your hands. So Segundo took the board and he wrote this: ‘Adriano, I do not fear anything of you, because you are the prince at this time. You may kill me, but you will never be able to hear my words.’ Adriano read this and he said “You have been excused, but first you must tell me some things. The first thing I want you to tell me is, ‘What is the world?’” The philosopher wrote: ‘The world is a circle that continues to move; it is beautiful to see, a creation that holds many forms.’ “What is the great sea?” said Adriano. The philosopher wrote ‘It circulates the world, made up of rivers from the source of rain’. “What is God” said the emperor. Segundo wrote, “An entity that will never die, the highest being that we must not undermine, a form that takes many shapes, he cannot be seen, he never sleeps, he embodies everything and is the light with not end.’ “ What is the sun?” ‘The eye in the sky, the circle of heat, the lucidity that never decays, it honours the day and departs at night.’ “What is the moon?” ‘The purple ornament in the sky, envious of the sun, enemy of the criminals, it aids those who walk, governing those who walk above the sea, symbol of the parties, demonstrating the storms.’ “What is the Earth?” ‘The ground below heaven, the yolk of the Earth, it keeps and mothers the fruits, it covers hell, mothers those that are born, loves those that live, destroyer of everything, dispenser of life.’ “What is man?” ‘The incarnated will, the ghost of time, the lurker of life, the servant of death, he who walks along the path and hosts intelligence [...].’ All of these things Emperor Adrian asked of the philospher Segundo, and he answered, writing all of his responses on the slate. And when the Emperor Adrian had completed all of his business in Athens he returned to Rome.

What Happened Next

Finally, the plays of the Golden Age also used the Estoria de España in search of plots for their comedies. For example, the famous play by Lope de Vega El mejor alcalde, el rey, about an honourable villain who has to appeal to the king for help when the lord of the lands commits a crime against him. Lope’s work is a dramatic development of a story from the reign of Alfonso VII that the Wise King included in the Estoria from Lucas de Tuy’s work Chronicon mundi.

The Estoria in the Cinema

The Estoria de España was used to transmit themes of the famous Cid to the modern world. The work itself used sources such as Las particiones del Rey Fernando, the Cantar de Sancho II and a version of the Cantar de Mio Cid (which was very similar to the famous manuscript by Vivar). Likewise, it used the Latin biography of the hero, known as the Historia Roderici (1180) and another work, la Cronica najerense (1185). It also used the work by the Arabic Historian Ibn Alfaray about the Cid’s territory in Valencia, as well as la Elegía de Valencia by Alwaggashi (1094). Finally, it used the brief text from Navarra called Linaje de Rodrigo Diaz (1094) and also the Leyenda de Cardeña, a series of semi-hagiographies about Rodrigo Diaz composed in the monastery of San Pedro in the middle of the 13th century. These works would have remained unknown today if it was not for the Estoria, as the original versions have been lost; between them there are the Leyenda de Cardeña, that tells one of the more memorable episodes of the life of the hero: the famous victory of the Cid after his death. This narrative was so striking that it moved the American film director Antony Mann to use it in the closing scene of El Cid. This famous work of cinema featured Charlton Heston and Sofia Loren, and included academic input from Ramon Menendez Pidal (a distinguished scholar of Spanish history). In short, the script of this well-known film would not have been the same without the work of the Wise King.

El mejor alcalde, el rey

The Emperor’s Justice

Don Alfonso, the emperor of Spain, was a very fair prince he brought justice to the robberies and misdoings in his land as we will see now. A lord that lived in Galicia called Don Fernando stole the property of a worker. And the worker complained to the emperor, who was in Toledo, about the theft. And then the emperor sent his letter with the worker to the judge who then saw the letter of complaint to see what rights he had. He sent a letter to the Lord, and as he was very powerful, he saw this letter he was very angry and began to threaten the worker and said that he would kill him and that he does not have any rights.

When the worker saw that he had no power over the lord he returned to the emperor of Toledo with the letters from the good men of the land to prove this. When the emperor heard this he called his servants for them to tell them not to allow anybody to enter his room. And he sent two gentlemen to secretly prepare his horses and to accompany him. And so they headed towards Galicia without stopping day or night. And so the emperor arrived at the place where the lord was, and he sent for the judge and demanded him to tell the truth. The judge told him everything. And as the emperor was now fully informed, he came to a decision and so he sent for the good men of the land. He demanded the lord to leave his house.

And when the lord heard him he was terrified that he would kill him and so he began to flee. But he was captured and brought before the emperor. The emperor explained everything to the good men. And as the lord had previously ignored his letter, he did not contradict anything. And so the emperor ordered for him to be hung from his own door. So the emperor had secretly travelled to Galicia and brought peace to the land. From then on everybody was respectful out of fear, and never caused harm to one another. And this justice, as well as others that the emperor had served, had caused the people to fear him and so everyone lived in peace.

Sounds From Another Time

In the second section of this display case we mentioned the importance of the Estoria de España for our knowledge of the medieval Spanish epic. One of the epics incorporated into the Estoria is the Mio Cid, in a versions very similar to that of the famous Vivar manuscript. In this clip, you can hear the beginning of the poem, in a recitation by the musicologist Antoni Rossell.