1. Pilot Design Group

As previously mentioned, the pilot Design Group was conducted at the National Library of Wales, which was in the midst of its World War I digitisation project encompassing a vast array of materials from the Libraries, Special Collections and Archives of Wales. The tens of thousands of digitised pages included diaries, letters, postcards, photographs, personal archives, army records and oral history recordings, and it was this range of different media present in the archive that meant compiling the digital resource posed significant questions and challenges to the design of the interface.

Given that we did not have much information about the scope of the digitisation, what equipment we would have to use, our participants or where the library were with their interface design, the approach we adopted was to start from scratch. We quickly developed a six session plan to divide the day and the seven participants were split into two groups. The first few sessions were aimed at introducing the participants to the themes of the resource and getting them to think about possible approaches. They were also able to browse and handle some source materials provided by the Library. In terms of design, they were provided with sheets of paper and firstly asked to think about how they might want to search for a particular topic or theme and how this might be represented on screen. The second piece of design work was taking a topic or theme into designing aspects of resource interface; search versus browse and visualisation. Finally, we regrouped to draw together the key themes of the day and to review any design work. (For the full report of the pilot Design Group see Appendix 3.)

We learnt a great deal from this pilot as it was clear that the participants were daunted by what they thought we were asking of them and intimidated by the blank sheets of paper. We drew four main conclusions to take forward to our own Design Groups. These were:

- It is essential to scope and clearly explain the aims of a session to manage expectations and emphasise that complete innovation is not a necessary outcome of the process so that participants are not intimidated by the task.

- It is easier first to critique existing resources before attempting to put pen to paper without any preparatory work. A blank sheet of paper can represent endless creative possibilities but is more likely to cause panic.

- Design Group sessions should be short and focused, concentrating on perhaps only one aspect of the interface at a time, as the process is quite intense.

- The group dynamic is important. A range of participant expertise in terms of the source material and familiarity with digital resources allows for a greater variety of ideas to be brought to the table. They will both ground each other and be able to think creatively and laterally.

2. Participant Profiles

Our Design Group was selected purposively. Individuals were approached who had taken part in focus groups, who were known to project team members and who sought us out wanting to be involved. A group of five was formed, representing almost the full range of disciplinary backgrounds we had selected for the project. The group were also at different career stages and a combination of expert and less expert in terms of both the source material and the use of online resources. A brief profile of each participant can be found below.

The five participants will subsequently be referred to using the following codes: RB, SE, JM, KR, MS. Their profiles reflect their status at the time the Design Groups were conducted and whether they had any previous experience of the test dataset or the current platform through which it can be accessed: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Roxanne But is a PhD student in the School of English at the University of Sheffield. Her PhD investigates the use of English slang words in historical texts. Through her research, in which she makes extensive use of electronic databases such as The Old Bailey Proceedings Online and The Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), she has also developed a keen interest in digital humanities. Roxanne was not previously familiar with the test dataset.

Scott Eldridge is a lecturer in Journalism Studies at the University of Sheffield. His research interests focus on understanding changing concepts, dynamics and identities of journalism in the face of new media technology and new media actors. He had no prior experience of EEBO or the test dataset.

James Mawdesley has recently (post-Design Groups) completed a PhD in the Department of History at the University of Sheffield. The subject of his thesis was ‘Clerical Politics in Lancashire and Cheshire during the Reign of Charles I (1625-1649)’ and as such he is familiar with the test dataset and uses EEBO, however, prefers physical archives for research purposes. He also took part in the pilot focus group.

Kirsty Rolfe had recently completed a Queen Mary-funded PhD at the beginning of the Design Group phase, working on the presentation of foreign policy in English printed pamphlets of the 1620s. During her PhD she also worked as a research assistant on Volume I of The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, ed. by Nadine Akkerman (forthcoming November 2014, Oxford University Press). She is currently a research associate for the Oxford Edition of the Sermons of John Donne. Kirsty makes extensive use of EEBO and uses the test dataset in her own research.

Michael Seymour developed his research interests in the test dataset as part of his PhD on pro-government propaganda in the 1650s, and has contributed to the work of Lancaster University’s Linguistics Department on these sources. Most recently, his work has been on the subject of the Atlantic in the early modern period.

3. Planning the Design Groups

Working from our observations of the pilot Design Group at the National Library of Wales, we designed a four-stage programme beginning with a preliminary interaction analysis workshop and followed by three Design Group sessions, which would more or less cover the aspects of interface identified in the original project plan: Working towards advanced search – search functionality and conceptual models underpinning search; Search results manipulation/visualisation and initial site interactivity; and Overall site interactivity and look and feel. The interaction analysis workshop would address the management of expectations, both our own and the participants’, and provide a forum for introducing the project and familiarising the participants with the format of sessions and what would be required of them. Within the sessions we developed a three-part iterative pattern of ‘critique – discuss – create’; hopefully, tackling the unease of being asked to design completely from scratch by first critically assessing and evaluating existing resources individually and then as a group. Scandinavian experts in Participatory Design endorsed this approach when we consulted them about its use in a humanities setting.

A closed social network was set up using Ning to provide a research community environment to post information about upcoming sessions, relevant articles and photos of workshop designs, to elicit discussion of anything arising from workshops meriting further thought, and to evolve and refine design ideas beyond the scope of our physical meetings, which were only three to four hours each in duration.

4. Design Group Formats

For each session the room was arranged into individual workspaces with a table in the centre to congregate around for group work. Each participant was provided with a desk, notepad, pens and post-its. They also used a laptop, either their own or provided by us. Our aim was to record as much of their interactions as possible, within their desk space and as a group. To this end, each participant was filmed on a digital video camera and video and audio recordings were made of group discussions and design work (figs 1-4). In addition, online screen capture software was used to record onscreen interactions. Each screen capture recording session was limited to 15 minutes. Participants were also encouraged to narrate their actions or comment on anything they were doing out loud.

Figure 1: Desk set up with recording equipment

Figure 2: Video still of desk set up

Figure 3: Room set up with prototype displayed on projector screen

Figure 4: Video still of group design work

5. Interaction Analysis Workshop

The Interaction Analysis Workshop was intended to provide a baseline for future findings and to introduce the group to the aims of the project and one another. The group formed a lively dynamic from the outset and each member contributed to discussions without the need for much prompting over and above ensuring certain points were covered and developing some of the emerging design ideas and conceptual thinking. During the workshop we asked participants to work on some of their own research specifically, by conducting searches for resources and references online. We then regrouped to discuss anything they had observed during this process, followed by a return to the laptop search to explore particular issues raised and finally regrouping to discuss further findings, jot down some initial design ideas (fig. 5) and evaluate the process as a whole. Much was achieved from this, including a huge amount of rich description of individual research practices and conceptual thinking (figs 6 and 7). In addition, it was comforting to find that many of the themes identified in the survey and focus groups were emerging again.

Figure 5: Initial design ideas

This design shows how the participants built on known sites to think about ways of representing the functionality they would expect and require in order to work with the newsbooks data. Here, they have begun to initiate ideas about displaying and working with search results.

Figure 6: Conceptual research network 1

Figure 7: Conceptual research network 2

These diagrams (figs 6 and 7) were drawn in response to asking participants to think about how they would go about constructing a search. It shows the structure of lines of thought surrounding a particular keyword or reference number and, from these points, the different directions the participant might explore to gather information around a central theme.

6. Design Group 1

To introduce Design Group 1, a summary of findings from the Interaction Analysis Workshop was presented to the participants. The findings were organised into three columns under the headings Observations, Critique and Suggestions. The project PI and Co-I then introduced the historical background of the Thomason Tracts and the project dataset. First, the participants critiqued existing resources (those suggested by us and/or used in their own research) with a particular focus on search and advanced search functionality. This was followed by a group discussion around the resources each participant had looked at and any particular observations. The participants then spent some time familiarising themselves with hardcopies of the source material and identifying possible research questions. The group reformed to discuss how they might wish to approach the source material from their own research perspectives and began to jot down some notes and comments around aspects of search functionality as well as setting down some initial design ideas on paper (figs 8-11). Our principal aim was to try to elicit from them how their conceptualisation of search might feed into aspects of functionality.

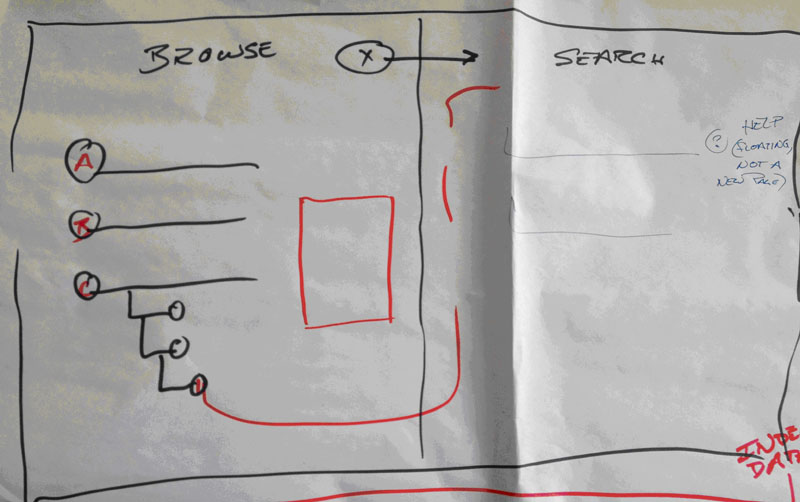

Figure 8: Search vs. browse

This diagram shows the group’s ideas for structuring search versus browse functions on the first screen and where contextual information or tooltips might be of use.

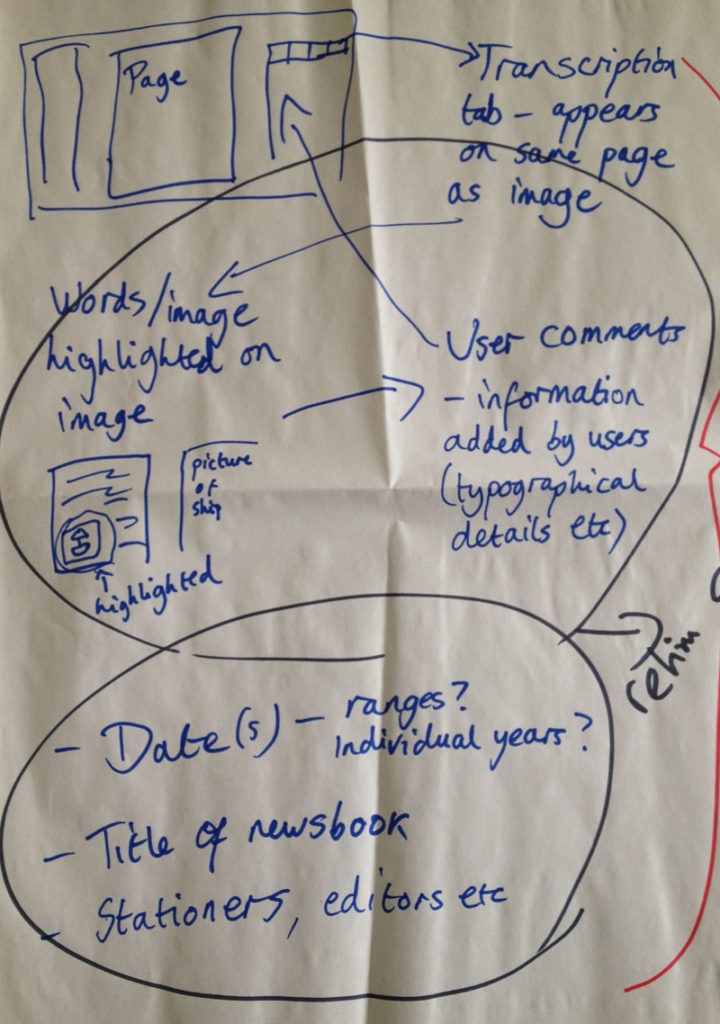

Figure 9: Result page

This design uses a copy of a page of the source material as the central focus of a result page with various tabs and sidebars providing desirable aspects of functionality. The group initially envisaged a series of layered tabs to provide a choice of transcription, annotations and comments, bibliographic details and so on. They were also thinking about the implications of an account function (represented by the smiley face in the top left hand corner) and ways of reporting errors or giving feedback.

Figure 10: Result page details

This design gives more detailed information about the results page tabs and what they might offer the user.

Figure 11: Tag check/discard function

7. Design Group 2

Ahead of Design Group 2, the specification arrived at with technical developers (which will be discussed in 2.3) was shared with the participants, to ensure transparency of the process and in order for them to observe their influences coming through in the development of the resource. To begin the session, they used and critiqued the first iteration of the resource prototype. They reacted positively to it, seemingly encouraged by what they saw, impressed with the functionality and intuitiveness already present, as well as being able to see that their ideas had had a significant impact on the design. Once again, they went on to critique existing resources (those suggested by us and/or used in their own research) with a particular focus on search results and site interactivity. We discussed their observations as a group and then moved on to reviewing and evolving their design ideas (figs 12 and 13), with the prototype as a reference point.

Figure 12: Results page, tagging and networking sketches

In this session, we spoke a lot about conceptual approaches to search and therefore there was a lot more to be gained from the analysis of the transcriptions than from the fairly minimal design work on paper that was achieved in the session. However, in the above drawing the account idea surfaces once again, as does a saving/discarding results function. The networking of sources was something the group returned to several times. It is not within the scope of this project but could be something to thing about for future development potential as it is becoming an increasingly sought after feature for a variety of research purposes.

Figure 13: Search pathways and tabs sketch

The top design shows a visualisation of a search pathway. The group spoke about how this could be represented in a resource and how it might be useful to them in terms of tracing routes through digital repositories and being able to find their way back to particular points to then branch off in new directions, and perhaps somehow even recording this process. The bottom design returns once again to the idea of tabbing but this time retaining a series of search results using a tab system, much like what can be done using the web browser itself but internal to the site in this case. The group thought this could be useful for comparing results.

8. Design Group 3

During the final Design Group, we were keen for the participants to focus on testing and refining the next iteration of the prototype. They first spent 30 minutes using and critiquing the prototype exclusively and the remaining time was devoted to discussing their impressions of it and evaluating it critically from their own research perspectives. We talked about the overall interactivity of the resource and its ‘look and feel’, in line with the aspects of interface to be covered in the project plan; however, they did not have a great deal to say about this or much they wanted to change, confirming themselves happy with its general appearance. There was a great deal of useful feedback received to aid the developers in tweaking certain aspects of functionality, particularly the account system, but no major amendments or additions were requested.

9. Assessment of Approach

The 3-part iterative session pattern of ‘critique–discuss–create’ seemed to facilitate the participants in thinking creatively, working from their own research practices and accommodating these in their designs for search functionality and beyond. The combination of discussion with pen and paper design work proved to be an inclusive way to operate as some group participants were less comfortable committing their ideas to paper, finding it much easier to express themselves verbally, while others were much more at ease with the idea of setting their thoughts down as drawings and diagrams. This is demonstrated in two extracts from the Interaction Analysis Workshop transcript below.

9.1. Extract 1

MS: “… I don’t think in terms of drawing things, I’m very textually orientated. I would have enormous trouble trying to illustrate a thought other than working harder at the vocabulary. I wouldn’t be able, I wouldn’t feel comfortable.”

SE: “Whereas…”

KR: “Yeah I really like illustrating things.”

9.2. Extract 2

MS: “It’s one of those things where I feel about the way this conversation’s going rather like I do when in the past I’ve had conversations with people about astrophysics. I understand the words they’re using and what they say when they say it but I couldn’t actually formulate a statement for myself but I recognise in what we’ve been hearing things of huge value for the sorts of things that I would want to do and in that sense I’m an unhelpful participant in that I’m in the category of I couldn’t tell you what I want but I’ll know when I see it.”

10. The Participant Experience

10.1. Roxanne’s Experience

“Overall, I really enjoyed my involvement in the Participating in Search Design project. I was particularly drawn to the project’s idea of the user as designer in the development of an electronic database, being able to make important decisions about what the search interface should look like, and thus create a database that would suit the needs of as many people within the research community as possible.

“During the Design Group sessions, we had to discuss our expectations and perceptions on what our ‘ideal’ database would look like, as well as getting our hands dirty and playing with the database prototype to critique what works well and what could be improved.

“This combination of theory and practice worked out really well, because during each Design Group session we were able to see for ourselves the things we suggested and which were implemented in the prototype. It does not happen very often that you get to see your own ideas so clearly translated into the actual design of something; it feels great to know that your input is much valued, and that you are making a real contribution to the final product.

“I also liked the engaging and fruitful discussions about the database with the other ‘design’ users. Because each of us came from different backgrounds within the humanities and social sciences, we all brought our unique perspectives and needs to the table, but we also found surprisingly much common ground in terms of our feedback on the database prototype.

“In addition, discussing our experiences in using the database helped me to communicate my ideas and thoughts in better ways. The project leaders did a fantastic job in encouraging me to explain things more clearly and explicitly, which was sometimes somewhat of a challenge when it comes to talking about something as subconscious as doing keyword searches!

“I’m very glad that I could be part of this new research experience, and I hope the results of this project will bring us a step forward into the improvement of search interfaces and overall research practices within our research discipline in general.”

10.2. Scott’s Experience

“I am not a historian. I do occasionally work in journalism history; I have written on histories of journalism technologies, but I am not a historian. Instead, I came to this project as someone who is interested in digital technologies, both for journalism studies and archival work. As it turned out, the Newsbooks project was a welcome and beneficial opportunity to work both with a historical archive with emerging digital technologies, and with an interdisciplinary set of scholars. During the years of the Newsbooks project, I was also working from time to time with the British Library to improve their resources and search tools for broadcast archives, so I was coming at search from several angles.

“This project offered a chance to approach the historical archives of the newsbooks from the vantage point of a contemporary journalism scholar, and to contribute to the project the perspective of someone who looks at modern dynamics but might want to address historical foundations. I am also someone who wanted to be able to do this sort of searching and scholarship without having to re-learn approaches to data searching, and without having to learn a specialised approach to studying archived material.

“For journalism studies scholars, having a more accessible way to explore journalism’s history can open new avenues of research and the ability to assess ‘regular’ journalism’s earliest versions, and there have been many calls for such historical perspective to ground new scholarship in more reflexive historical bases. This has been lacking in a lot of contemporary scholarship, and this fuelled my interest in the project. Yet I still felt I was an outsider, and at the first meeting of the design group, when everyone was introducing themselves and the other participants said they studied topics like The English Civil War, Clergy, Linguistics, Newsbooks themselves – scholars of the 17th century – my response was: ‘WikiLeaks’. Hardly historical. My clearest admission of ill-fitting? ‘What is EEBO?’

“That said, once we began working collaboratively we saw a variety of cognate interest – the use of certain language, the transmission of information, and most importantly, locating the best ways to access archival information. In this aspect, I found that my lack of in-depth awareness of the subject material was an asset. Having worked with a range of archives and digital search tools across my academic career, I felt intimately aware of what certainly didn’t work. We began discussing the ways in which libraries referenced, presented, and connected their work and archives, and while for some certain standards of referencing and reference data was the ‘norm’, that level of specificity would not be as familiar or useful for journalism studies scholars. These points informed the way we talked about what we wanted in a search tool, and we worked to find ways to envisage one that could speak to a wide range of scholars.

“Drawing on my own work I also had an idea of what tools were possible and advantageous for archive tools and search tools, and in our design group’s meetings and discussions, we started to realise that search has some core similarities, regardless of the research for the search. As we began progressing to prototypes, I found that we were not only on the same page, but each put our expertise to use to hone the prototype: Some searched for items that resonated with their research, I tried ‘breaking’ the prototype and assessing it as a digital tool, a search tool, a tool for someone who’d never heard of ‘EEBO’.

“In the end, I was pleased not only with the tool, but with how it came to be built, and I found myself thinking of how I could integrate such a tool into my own work, contemporary in focus but with historical grounding.”

10.3. James’s Experience

“I have found being involved in the Design Group to have been a very useful experience. It has given me an insight into the design and workings of these sorts of large databases, and as such, I have been able to market in my academic CV the experience, which I have gained from participating in a collaborative research and design enterprise. This experience allows me to demonstrate that I am not just a historian who simply lurks in archives, but that additionally, I have played a role in this sort of web-based design project, and I possess the skills I can apply to such projects in the future. I am looking forward to playing some sort of role at the forthcoming project conference on 17th Century Journalism in the Digital Age (22nd November 2014) at which I will be able to network and publicise both my own work, and the potential of the database.”

10.4. Kirsty’s Experience

“The ‘Participating in Search Design’ project appealed to me because I use digitised resources – especially Early English Books Online – a great deal in my own research, and early modern news pamphlets are a topic I’m particularly interested in. EEBO and other digitised resources have been absolutely invaluable (I couldn’t do the research I do without them) but there are some aspects of the search design and interface that I find frustrating when it comes to my own research questions. I wanted both to learn more about how these are decided upon, and to see if it might be possible to address some of my frustrations in order to make it easier to ask the sorts of research questions I want to ask.

“I also had a more theoretical concern: in terms of research ethics, I don’t like how easy it is as a scholar to slide into a way of thinking of digital resources as merely a sort of box into which documents are put, which can be easy to use or frustrating to use but which isn’t itself a scholarly work that has taken a great deal of labour (intellectual and physical) to put together. This way of viewing something like EEBO is both dangerous to scholarship (it risks discounting the influences that EEBO as a means of accessing and reading texts will have on how we read those texts, and on which texts we read), and perpetuates unhelpful and unfair divisions between those who produce and maintain websites and databases and ‘users’. I certainly wouldn’t say I know what I’m talking about when it comes to the technical side of the search design process, but participating in the workshops has really prompted me to think of digital scholarship as a matter of co-operation between colleagues with different skill sets – and as something that I can learn more about, and influence in (hopefully) helpful ways. The workshops allowed us to learn more about what’s possible on the development side, and I think also helped the developers to understand what users might appreciate in some concrete ways. One example of this is that we were really keen to have individual accounts where users can save documents for future reference, but thought that this might be a bit tricky to implement. In fact, the developers were happy to do it but were wary because they didn’t think people would use them. This feature is certainly something that will be very useful indeed for my own research – I think it’ll change how I can use these texts in a very positive way.

“I really enjoyed being part of the group – the workshops, and the communication outside of them, were very well organised. I was really impressed with the work the developers put in – it was great to be able to try out and critique actual prototypes and this added to the feeling that our input was having tangible results. One thing I wasn’t really expecting was how much I learned about my own research methods – describing what I was doing for the recordings revealed that I was rather more systematic than I’d suspected! I also learned a lot from hearing the other members of the group describing their own research processes. It was great to have such a range of expertise and methodologies in the room: I felt this was a major strength of the project, as hopefully it’ll mean that the interface is as useful as it can be to a wide range of scholars.”